Simona and the Forest of the White Tower

We should finally acknowledge that Earth is not our property. We are only co-tenants of Earth and we could, in a way that would not be too costly for us, curb our appetites and let all those other creatures live.

–Simona Kossack

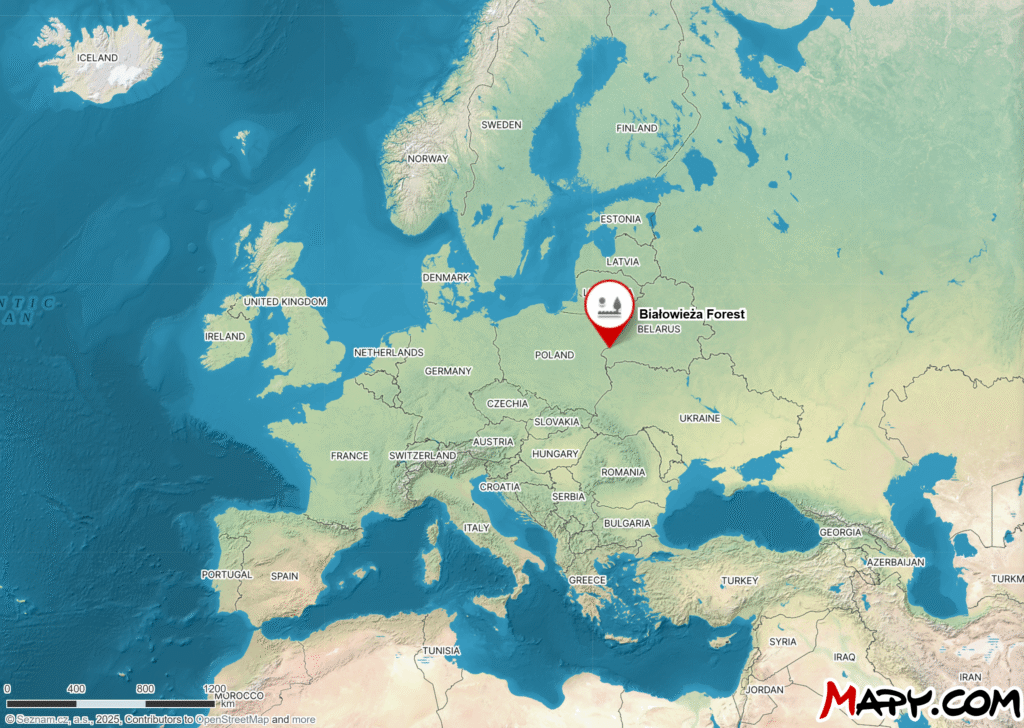

Before modern human civilization reshaped the planet, a vast primeval forest blanketed the Eurasian Plain, from the Urals in Russia to the French Pyrenees.

These woods were verdant, the dense, green-bearded backdrops that inhabit the worlds of the Brothers Grimm and J.R.R. Tolkien. For much of the Common Era, the forest was so thick that human travel in many areas was relegated to the rivers. It was a deciduous, European analog to the Amazon Rainforest.

As the human population boomed, the forest’s area suffered a corresponding decline. Over the centuries, massive swaths disappeared.

Today, less than 1% of these majestic tracts survive. Small patches in the Carpathians, Germany, and the Baltic remain as ancient spits in a contemporary ocean. The largest remaining parcel is located on the border between Poland and Belarus. The Białowieża Forest – Polish for “the Forest of the White Tower” – is half the size of Rhode Island and slightly larger than Hong Kong.

Its 550 square miles are all that’s left of a continental forest in its original state.

What remains of the Białowieża Forest is a natural and historical miracle.

Despite the general trend of deforestation, humans in the region recognized Białowieża for protection centuries ago. This rare honor stemmed from its special inhabitants. It was the subject of one of the first pieces of legislation to protect fauna, as a 1538 law forbade the hunting of European bison, also known as wisent or aurochs.

Yes, even today, Białowieża Forest has bison, though the wisent there have not had an uninterrupted existence. Multiple times since the 16th century, leaders have opened the forest to hunting. As we know well in North America, when culling runs wild, things don’t end well for the bison. Both World Wars brought encroachment from foreign armies. Białowieża lost biomass both times, and the animal numbers dwindled. After World War II, the population of wisent in Europe was perilously low, essentially banished to zoos.

Thankfully, we decided collectively to reintroduce them to their native habitat.

So, bison were in Białowieża to greet a new human resident in 1975, a woman who would become their biggest advocate.

“It was the first wisent that I saw in my life – I am not counting the ones in the zoo. Well, and this greeting right at the entry into the forest – this monumental wisent, the whiteness, the snow, the full moon, whitest white everywhere, […] and the little hut hidden in the little clearing all covered with snow, an abandoned house that no one had lived in for two years. In the middle room, there were no floors; it was generally in ruins. And I looked at this house, all silvered by the moon as it was, romantic, and I said, ‘it’s finished, it’s here or nowhere else!”

These were the recollections of Simona Kossak on her first foray into Białowieża Forest.

The daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter of notable Polish painters, Kossak veered away from a lineage in the fine arts and toward animals and science. Born in Kraków during World War II, she attended the Jagiellonian University, studying animal behavior and psychology. After graduation, she began working for the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, located in Białowieża Forest.

The primeval woods called to the young researcher so starkly that she requested to live in a dilapidated lodge deep in Białowieża. When she first caught sight of “Dziedzinka” – with a little help from a wisent – Kossak knew her life belonged there.

When she moved into the house, Simona Kossak embarked upon a life that makes Henry David Thoreau’s outing to Walden look like a stroll in a park.

She planned to study the forest from this base largely in solitude, but found, by happenstance, that another intrepid soul had sought to live in this same rustic outpost. Though she and Lech Wilczek initially disliked each other, they quickly realized they had much in common.

One day, Wilczek discovered an orphaned baby boar and brought it to the lodge. Kossak, who had tended to injured animals in her youth, took in the critter, raising the boar to adulthood. Żabka – “Frog” in English – became part of the family, a unit that now included Wilczek.

He and Simona became lifelong partners. They lived at Dziedzinka for over 30 years, without running water or electricity, through the harsh Polish winters. Kossak examined the forest as a scientist, while Wilczek, a photographer, documented their lives.

Żabka was the first non-human resident at the lodge, but hardly the last. There was Korasek the crow, deemed a “terrorist,” a “tamed villain,” and a “thief” by visitors. He would attack anyone – human or otherwise – that wasn’t Kossak or Wilczek. She reared twin Moose, Cola and Pepsi. There was Agata, a lynx, who, like Żabka, sometimes slept with Simona in bed.

If the rugged life in the wilderness didn’t seem too extraordinary, this last sentence about shared slumber should put any doubts about the exceptional nature of Kossak’s life to bed.

Kossak integrated herself into the forest in a way few humans have ever attempted (Jane Goodall comes to mind). She looked to break down the barriers we’ve created between ourselves and the natural world, approaching a life that we might have inhabited millennia in the past.

If this life sounds fictional, let the incredible photograph of Lech Wilczek fill the void.

Kossak’s deft touch and unique lifestyle allowed her to become part of the entire biome, not a human set apart.

Consider this remarkable anecdote:

“One day, the pack of my deer, which I raised and fed with a bottle, and which I later followed across the woods for many years, manifested signs of fright, and did not want to go out onto the forest field to graze. And I started to approach the young forest, because this was the direction in which the deer started, their ears raised, and the hair standing up on their buttocks, apparently something very threatening had to be there in the young forest. I crossed about half of this open space, and I stopped, because I heard a choir of terrified barking behind me, so I turned around, and what did I see? […] Five of my deer stood up on their stiffly straightened legs, looking at me, and calling with this bark: don’t go there, don’t go there, there’s death over there! I must admit, I was dumbstruck, and then finally I did go. And what did I find? It turned out that there were fresh traces of a lynx that had crossed the young forest. I went in deeper, and I found lynx faeces; it was indeed warm, because I touched it. What did that mean? It meant that a carnivore had entered the farm, the deer noticed him, then ran and they were scared, and what did they see? They saw their mother going unto death, completely unaware, she had to be warned, and for me, I will honestly admit, this day was a breakthrough. I crossed the border that divides the human world from that of the animals. If there was a glass that divided us from humans, a wall impossible to knock down, then the animals would not care about me. We are deer, she is human, what do we care for her? If they did warn me […], it meant one thing and one thing only: you are a member of our pack, we don’t want you to get hurt. I honestly admit, I relived this event for many days, and in fact today, when I think about it, there is a sense of warmth around my heart. It proves how one can befriend the world of wild animals.”

Though I have bonded immensely with domestic animals and cavorted with a few wild ones, this experience seems rare and profound. Most modern humans, I assume, live with the belief of the glass wall that separates us from the animal world. Need it be that way?

Kossak’s integration into the forest wasn’t just soul-filling as an animal lover, she did hard science along the way.

She received a doctorate and post-doctorate degree in forest science, penning Research on the trophic situation of roe deer in the habitat of fresh mixed coniferous forest and Environmental and intraspecific determinants of the feeding behavior of roe deer (Capreolus capreolus L.) in the forest environment. She became a Professor of Forest Science at the Polish Forest Research Institute in Warsaw. In 2003, she became the Institute’s director.

During her studies, she helped develop the UOZ-1 repeller, a contraption that emits acoustic signals to animals when a train approaches on nearby tracks. The device demonstrably reduces collisions.

Her love for Białowieża and its inhabitants took a more tangible slant, too.

She discovered scientists illegally using potentially lethal traps to tag wolves and lynxes. Though the tracking program was worthy, the methodology endangered the animals.

During court hearings on the subject, Simona argued:

“Each animal that falls into the trap is potentially condemned to die, if the wound to the paws is heavy. With a population that numbers 12 specimen, and including poaching and chance deaths of wild animals, it is a lethal threat to the continuity of the lowland lynx type, whose genetic scope is unique across all of Europe, because there are no more lowland lynxes in Europe. It is a disgrace to the world of science for us to have contributed to this.”

Her advocacy wasn’t always so confrontational, though. Perhaps her greatest public service arrived thanks to a radio program she hosted, called “Why Is It Squeaking in the Grass?” During episodes, she shared her life with animals, providing insight into the worth of the primeval forest. The show helped sway public sentiment for preserving the location.

She wrote two books, The Białowieza Forest Saga and The National Park in the Białowieza Forest.

All the while, she remained a resident of the woods, cavorting with animals as equals.

When Kossak died in 2007, the future of the Białowieża Forest looked wonderful. Both a National Park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, we seemed to have ensured that this special place would remain untouched.

However, more than 84% of the Polish part of the forest lies outside the National Park. Since 2016, some Polish politicians have advocated for logging the ancient wood of Białowieża. The environmental minister announced a tripling of cuts in the area, under the guise of combating a beetle infestation and questioning the true age of the forest.

Kossak would, of course, be horrified at such a move.

Few people have the gumption and clarity to live a life of conviction like Simona Kossak. Though most of us could never live up to such an example, now that she’s gone, we must do what we can to save the Białowieża Forests of the planet.

Further Reading and Exploration

The Extraordinary Life of Simona Kossak – Culture

Simona – Film Documentary

Prof. dr hab. SIMONA KOSSAK – Forest Research Institute

A Paradise Called Dziedzinka – Prze Kroj

Białowieża National Park – Official Website

Białowieża Forest – UNESCO