Light Pillars, 22° Halos, Tangent Arcs, Bottlinger’s rings, Parry Arcs, and Circumzenithal Arcs, and More!

In our two previous articles, we discovered diamond dust and sun dogs. While these phenomena are righteous on their own, they are singular manifestations of a larger class of optical splendors. They both arise thanks to ice crystals in the atmosphere. When these crystals reside near the surface we call them diamond dust; when they happen higher in the sky the crystals can produce visual objects called halos. A sun dog is one type of halo. Looking at today’s title – which takes its inspiration from an earlier meteorological article – you might sense sun dogs are one type of many halos. You would be correct!

In fact, so many examples occur that today’s title could be much longer.

What follows is a primer on some of the more extraordinary and interesting examples of halos. Each one might merit an investigation on its own, but, for the sake of brevity and the restrictions of the theme-week medium, we’ll lean on quick introductions and revel in some vision confection.

Sun dogs radiate from the light source horizontally. When ice crystals shoot light vertically we might receive a treat called light pillars.

The images above are sun pillars, but, just as with sun dogs, the moon can also create pillars.

Further, pillars are one of the few phenomena that might be even more resplendent artificially than naturally. If conditions are right, human-made lights can produce spectacular pillars, as in the second photo below.

Perhaps the example that best demonstrates the overall spirit of halos is the 22-degree version.

You might recall that sun dogs appear 22 degrees away from the sun, which is approximately the length of a hand when one stretches out an arm. In some of the more dramatic sun dog images, the beginnings of a circle might appear. Sometimes the geometry completes itself, forming a 22° halo. As with sun dogs, this degree refers to the angular distance from the light source, not the angle within the circle itself. So, the circle’s radius is about a hand’s length around the source.

These halos are quite striking. When the halo forms around the moon we call them moon rings or winter halos.

In the image above, you can see the halo is joined by sun dogs at the edges. It also features a tangent arc.

If you recall geometry class, a line is a tangent to a circle if it touches the circle at just one point. In optical phenomena, tangent arcs work the same way, touching the 22° halo either above or below the sun.

Bottom tangent arcs are difficult to see from ground level, so the one in the image above is a bit obscure. Elevated positions or airplane rides offer better views. We can capture upper tangent arcs photographically with more ease:

The combo of ice crystals and light can produce a few other types of arcs, as well.

Humans sometimes confuse two of them for rainbows, as they feature colors in the same way. A circumhorizontal arc – sometimes called a fire rainbow or a circumhorizon arc – is a band near the horizon. They can form with circular halos or just in patches of clouds.

A circumzenithal arc forms above the light source, approximately 46 degrees higher. Other monikers for this arc are the upside-down rainbow or Bravais arc. These arcs are sometimes characterized as “smiles in the sky.”

This arc can form up to a quarter of a circle.

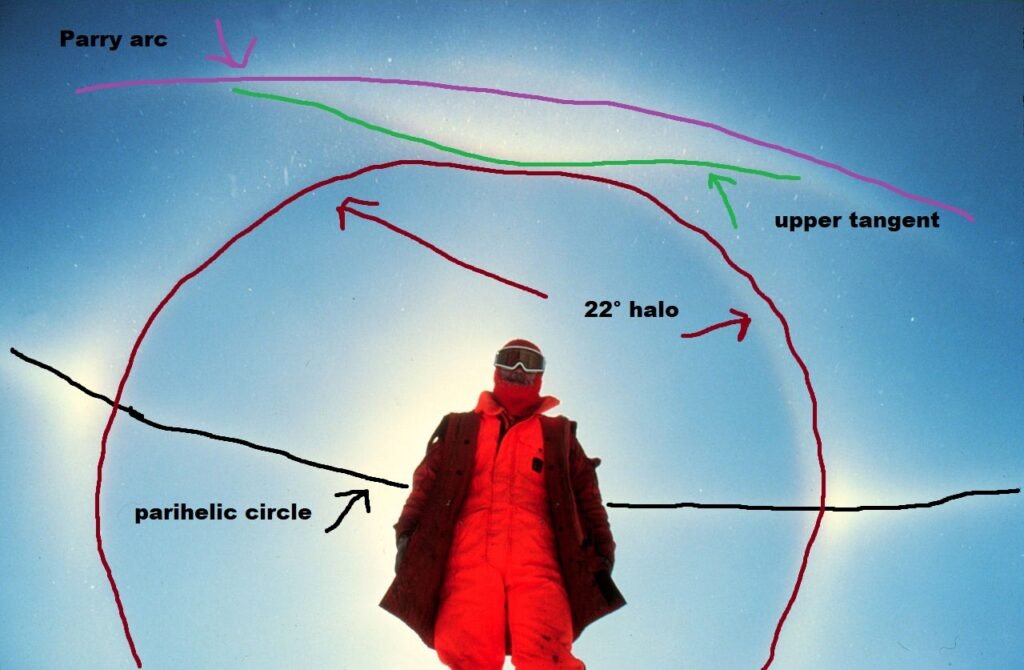

Sometimes a faint arc forms on top of the upper tangent arc, which opens upward. These formations are called Parry arcs. A faint Parry arc is visible in the photo above.

Occasionally, a horizontal line will stretch from the sun or moon. These lines can connect with circular halos and might even stretch across the entire sky! These lines we dub parhelic circles.

Some of the greatest displays feature multiple types of halos, which makes it helpful to differentiate all these confusing names. In the image below, the parhelic circle is the horizontal line; the circle is a 22° halo; the blobs on the sides are sun dogs; the v-shaped arc on top is an upper tangent arc; on top of that is the downward-facing Parry arc. There will be a quiz at the end of the article.

Sometimes the shapes get tricky. In geometry, a circumscribed circle is one that passes through the vertices of a polygon. In optical phenomena, sometimes a circumscribed halo arises, where an oval circumscribes the 22° halo.

These two circular forms can be trippy:

As incredible as the clean appearance of the 22° halo is, one of the universe’s true wonders is a far rarer halo: the 46° halo.

This halo is formed the same way as its closer cousin and appears in tandem. The 46-degree version is just over twice the distance from the light source. The formation of two perfect circles around the sun or the moon is a stupendous sight.

We could continue to explore these icy examples of atmospheric optics until the sun’s death. And we haven’t even touched supralateral or infralateral arcs, Lowitz arcs, Moilanen arcs, Kern arcs, 44° parhelia, 120° parhelia, subhorizon arcs, pyramidal halos, and numerous others. The breadth of displays is staggering. If you’re interested in learning more about the instances we explored or those we did not have time to investigate, check out the Further Reading and Exploration section below for some extracurricular reading.

I promised a quiz somewhere in the middle of the article. You’re off the hook. I can’t expect you to recall all this information so quickly. Simply enjoy the light in our lives!

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.