The Ripening of the Banana

You’re in a supermarket.

As you sashay through the produce department, you decide to procure some fresh fruit. Pondering which sweet foodstuff to take home, the yellow catches your eye.

Ah, yes. Bananas. You love bananas. They’re just the right amount of ripe, too. Mostly yellow with a hint of green at the stem. By the time you eat this gem, it will be perfect!

You take your soon-to-be-perfect banana home. Two days later, you peer at your fruit bowl to see a blackened banana. With a sigh, you wonder, “how did this piece of fruit make it all the way from the tropics to my house unruined, only to overripen before I can even enjoy it?”

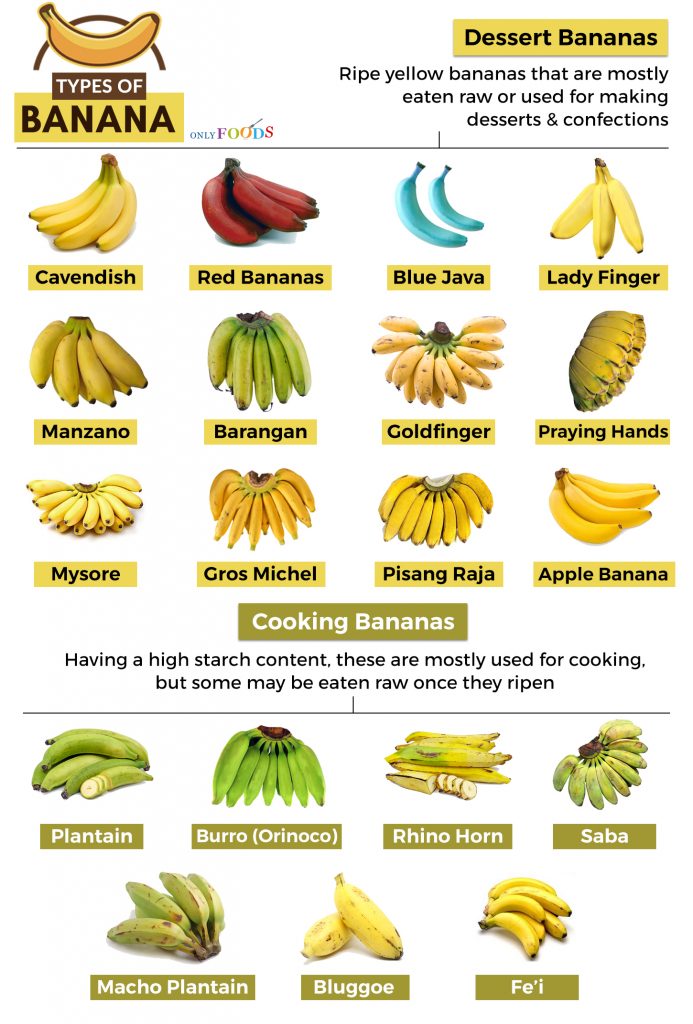

If you live in the United States, you most likely purchased a Cavendish banana. Though the style we most often see in the supermarket might seem singular, bananas are closer to apples when it comes to variety: over 1,000 types exist across the globe. In fact, they are not even all sweet. Dessert bananas, such as the Cavendish, differ from cooking bananas, which we sometimes call “plantains.” Bananas are also technically berries! They do not grow on trees, as we commonly believe, but on a plant in the herb family.

If you live in the United States, there’s a good chance the banana you bought features one of these stickers:

Most bananas grow close to the equator. They are native to southeast Asia and Australasia, though more than 150 countries now grow them in the tropic band. So, how does a fruit manage to make it all the way from South America or Central America to your supermarket at just the right level of ripeness? Do Chiquita and Dole have the timing of the supply chain perfectly honed?

In a world with shipping disruptions and mammoth cargo ships stuck in canals, you would be wise to ask that question with skepticism. The answer is yes, but not for the reason you might imagine.

The secret is gas.

Companies harvest bananas when they are still green. Under normal circumstances, they would never reach store-yellow. A contrived sequence under precise conditions produces the yellow color ubiquitously associated with bananas.

After picking, bananas are shipped in cooled containers. The temperatures must remain between 56 and 59 degrees Fahrenheit. If the banana gets too cold, it will never ripen and, instead, start to degrade. Under 56 degrees, bananas become grey mush if they have not yet ripened. If they have ripened, you can store a banana in a refrigerator. Its peel will turn black, but the fruit within will remain edible. To become yellow, however, retailers must generate ripening. They do so with a gas called ethylene.

Merchants store bananas in special, airtight rooms. Filling these rooms with ethylene will trigger a banana to ripen. Retailers can control the amount of ethylene introduced. If bananas in the produce department are waning, more gas will ripen green ones faster, replenishing bare racks. If bananas are not flying off shelves, less ethylene will keep the backstock at just the right trajectory.

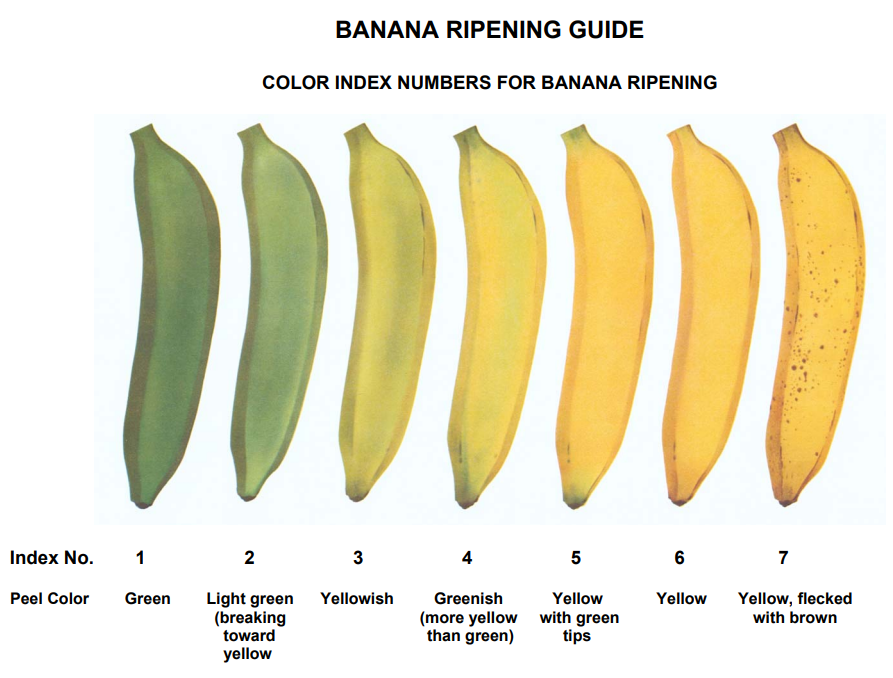

The industry uses a scale from 1 (green) to 7 (yellow with some black dotting) to rate the state of a banana’s ripening. Most humans prefer bananas between 5 and 6, though many enjoy a fully ripe 7 or an underdeveloped specimen. It is this behind-the-scenes timing that matters most when it comes to your banana’s home life.

Once the ethylene gas hits the banana, the race is on. The mistake we make is to view the development of a banana’s color as a continuum from the moment it’s picked. If you assume the fruit took a lot of time to pass through the Panama Canal to reach your store, you’d be correct. What’s a day or two on this timeline? If you assumed just one or two more days after seeing a bright yellow fruit is safe, ethylene gas would like to have a word.

On the flip side, if you purchase a banana that is slightly under the ripeness you would enjoy, you can use ethylene to your advantage. Toss your banana in a bag with an apple. They both produce ethylene naturally as they ripen. In a day, your banana will be ready to go.

However, you should be willing to eat both the banana and the apple, as each will accelerate the other’s ripening process. Timing is everything!

BONUS FACTS: The banana is the world’s most popular fruit. I never would have guessed the world’s largest (by far) producer of the fruit: India!

Further Reading and Exploration

The Surprising Science Behind the World’s Most Popular Fruit – National Geographic

8 things you didn’t know about bananas – PBS

Why do bananas go brown and ripen other fruit? – BBC