The Wandering Meatloaf

Chitons are a class of mollusks specific to the oceans of the planet.

Unlike some mollusks with which you might be familiar, chitons appear more like blobby flapjacks than the normal shell topographies of a clam or a snail. When a snail feels threatened she can dive into her hard home; when an entity attacks a clam the gates close. But these organisms must remain in the panic room until danger clears. The physiology of chitons, however, makes them uniquely mobile.

Chitons possess a shell that is divided into eight valves, which function like plates of armor. Instead of forming a snail’s helix or a clam’s hinge, the armor of a chiton covers her like a blanket. This arrangement allows for protection and movement. When attacked, the chiton can roll into a ball, protected by eight scales. The layout, however, means the chiton can move over varied terrain while remaining protected, as the plates can flow over irregular surfaces as if they were tank treads.

These beautiful marvels of evolutionary engineering inhabit areas of the oceans with hard surfaces, often skittering about tidepools. Here’s how one looks and moves:

One species of chiton displays an array of fantastic attributes.

Cryptochiton stelleri populates the northern Pacific Ocean, along the upper portions of the Ring of Fire, from Central California to Alaska’s Aleutian arc, and down to Japan. This species is known by a few sobriquets, including the gumboot chiton, the giant western fiery chiton, the giant Pacific chiton, or, today’s title, the Wandering Meatloaf.

Why Wandering Meatloaf?

Pictures are worth a zillion words:

As you can see in the video above, the valves of most chitons are visible. For the gumboot chiton, the plates are covered by a leathery sheath that looks a lot like a slab of smushed meatloaf.

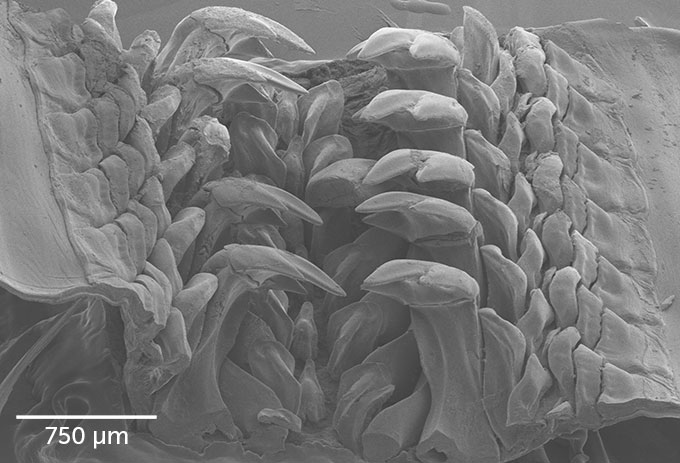

On the underside, chitons sport a foot, gills, and teeth. These chompers are composed of a mineral called magnetite, an iron oxide. The hard magnetite permits chitons to scrape algae off rocks. Yummy. Magnetite is more than three times as hard as the enamel on a human’s tooth!

While having teeth made of iron is undeniably metal, the meatloaf’s set packs an additional quality. This quality not only makes the gumboot unique among chitons but unique among all life on Earth!

Scientists recently discovered an interface between the meatloaf’s teeth and its softer body. This lattice includes a nanoparticle called santabarbaraite. Like magnetite, santabarbaraite is an iron-filled mineral. Unlike magnetite, it is named for Santa Barbara. Not the California community, but a mining district in Italy.

Santabarbaraite is a curious compound. We were not even aware of its existence until 2000 when it was discovered in Tuscany. For two decades, we only found this newly unearthed mineral in rocks and only in a few spots on the planet: Italy, Australia, and Siberia. Then, suddenly, it appeared in gumboot chitons!

What is this rare substance doing in the teeth of a sea creature? The working theory is the santabarbaraite’s properties allow its hardness and stiffness to change over extraordinarily small distances – just a few human hair lengths. These properties allow a small-scale form of the chiton’s tank-tread plate phenomenon, forming a pliable buffer between ultra-hard teeth and a super-soft body.

Great for the chiton, but, so what, you ask? When a rare material shows up in an unlikely biological location, scientists see opportunity. In this case, scientists have started to work with the structure and properties of santabarbaraite to create nanomaterials for robotics. Most robots are like snails: they can maneuver through easy terrain but struggle with small spaces. If researchers can develop an interface for necessarily hard robot parts and potentially malleable “body” components, perhaps we could see robots getting into previously impossible situations.

Maybe tomorrow’s bomb-defusing bot can reach locations currently inaccessible. The prospects for space exploration via rover seem limitless in this regard. Phenomenal to see the blueprints of nature advance technology!

Further Reading and Exploration

Gumboot chiton – Alaska Sealife Center

How the ‘Wandering Meatloaf’ Got Its Rock-Hard Teeth – New York Times

The teeth of ‘wandering meatloaf’ contain a rare mineral found only in rocks – ScienceNews

Persistent polyamorphism in the chiton tooth: From a new biomineral to inks for additive manufacturing – Northwestern University