Uranus Rains Diamonds

[This article is the third in a series on Uranus. Read Part I: The Tilting of Uranus and Part 2: Uranus Stinks to make sure you’re fully up to date with Uranus.]

We have certainly learned over the years that Uranus is a weird place. Uranus tilts and Uranus stinks, but, as we probe Uranus more and more, we know the oddities don’t stop there.

If one could magically transport to the inner portions of Uranus, one might discover that Uranus is a girl’s best friend.

Why, you ask?

Because Uranus rains diamonds.

Astronomers refer to Uranus and Neptune as the Ice Giants. They gain this moniker because their outer layers contain a lot of hydrogen, not because they are currently solid. At one point, the water, methane, and ammonia there were likely solid, leading to the nickname.

We have only explored Uranus (and Neptune) in depth a single time, as Voyager 2 reached Uranus in 1986. That mission and information we gather from remote viewing of Uranus gave us enough knowledge to model the makeup of the planet.

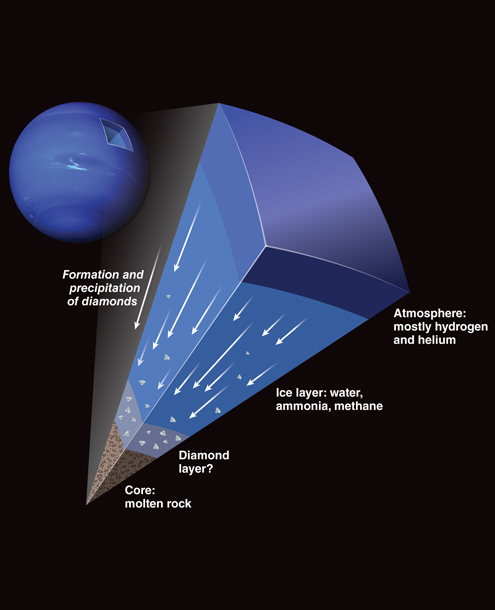

Despite the fact that 80% of Uranus is composed of liquid water, methane, and ammonia, it does have a rocky core. The outer atmosphere consists of the gases mentioned above. Between the two extremes resides a middle layer of gas; it’s here that things get interesting.

Mathematical models and computer simulations indicate that the gravity of Uranus compresses the gases of Uranus, raising the density and the temperature to points of several thousands of degrees Kelvin. That number is one that approaches the temperature of the surface of the sun. This compression also supercharged the pressure on the substances, increasing the force to more than a million times the pressure we feel atmospherically on Earth.

Under this incredible pressure, the gases of Uranus actually turn into liquid. Under these conditions, methane tends to break into its constituent parts, carbon and hydrogen. In this raucous soup, the carbon atoms find each other and form chains. And what is one form of pure carbon? Diamonds!

The high pressure now operates on the chains, forming crystalline diamonds. These new, denser structures begin to fall through Uranus, a process similar to water droplets in storm clouds on our planet. The diamonds rain toward the center of the planet, until they reach a point where the temperatures vaporize the chains. The carbon then floats back toward the “cloudy” areas where they used to be methane. Uranus has a “water cycle”, made of diamonds instead of dihydrogen monoxide.

Of course, no human has ever watched Uranus rain diamonds. Uranus is inhospitable. No one wants to go there.

Though scientists trust mathematics and their computer simulations, this phenomenon seems outlandish to everyday Earth life. So, researchers have devised increasingly sophisticated laboratory experiments to test the diamond rain of Uranus.

Using lasers, scientists can briefly replicate the temperatures and pressures of Uranus. They managed to produce extraordinarily tiny diamonds from styrofoam. Though it’s not methane, the compounds behave similarly when it comes to chemistry. Other experiments have tested methane, placing it between diamond anvils and heating it with electrical currents. These trials have also produced diamonds.

All signs point to diamond rain deep within Uranus. And Neptune, too. But Neptune makes for far less satisfying copy. Things just always seem better with Uranus.

Further Reading and Exploration

Yes, there is really ‘diamond rain’ on Uranus and Neptune – Space

On Neptune, It’s Raining Diamonds – American Scientist

Icy Planets’ Diamond Rain Created in Laser Laboratory – Space

On Neptune and Uranus, Diamonds Rain Down from the Sky – Popular Mechanics