Þrídrangaviti Lighthouse

Once they got near the top there was no way to get any grip on the rock so one of them got down on his knees, the second stood on his back, and then the third climbed on top of the other two and was able to reach the nib of the cliff above. I cannot even tell you how I was feeling whilst witnessing this incredibly dangerous procedure.

Outside of the United States, Iceland might be the nation with the most newsletter articles dedicated to spots within its borders. It’s gotta be number one in terms of episodes per capita or per square mile (375,000 people, ranking 172nd of 195 countries; just under 40,000 square miles for 106th on this list; a little surprised it ranks that highly in terms of size).

Despite its dimensions, this island packs rugged, outlandish beauty. We’ve investigated Kirkjufell, one of the world’s most recognizable mountains. We learned about the incredible power of ice and water in the form of jökulhlaups. Visited, too, Yoda Cave, did we. The cause behind the Worst Year to Be Alive might have been an Icelandic volcano. We discovered Iceland is home to more than 60% of the planet’s Atlantic puffins. The upstanding citizens of the nation even form puffling patrols to help wayward hatchlings having issues with artificial light. You can catch a heck of an aurora there, as well.

These topics represent just the, ahem, tip of the iceberg – we haven’t explored the hot-spot origins of Iceland, its thermal springs, or magnificent volcanic eruptions. I’m sure we’ll return many times in the future to look into these topics and more.

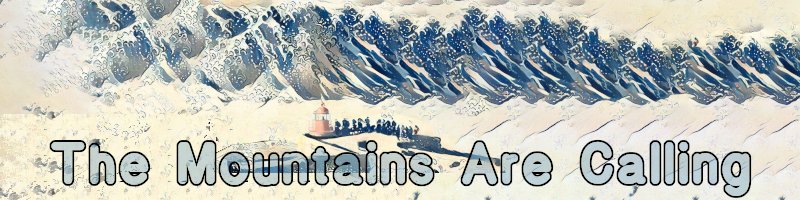

When I saw the following image online recently, though, I knew it was time to head back to Ísland once again:

Yes, that is a lighthouse on a sea stack.

I felt claustrophobia and vertigo just seeing the image, but this viewpoint is only part of the story.

The structure atop the rock is called Þrídrangaviti Lighthouse, which is transliterated to English as Thridrangaviti Lighthouse. The Icelandic moniker for the building comes from the name of the stacks; In Icelandic, Þrídrangar means “three rock pillars.” The lighthouse roosts on a stack called Stóridrangur, the tallest of the three in the formation. Amusingly, Google Translate equates Stóridrangur to the English phrase “Big Boy.” The other two are Þúfudrangur, and Klofadrangur, which decodes to “a thousand and one” and “cleavage,” respectively. I have a hard time believing these translations, but I want them to be correct. In reality, drangur translates to “rock” or “pillar.” Stóri means “big,” and klofa is “cleft,” but the exact implication of Þúfu is harder to discern.

Unlike the marvelous sea stacks at the Cliffs of Moher in Ireland, Þrídrangar does not sit just off the shore. Instead, the rocks rise five miles away from mainland Iceland in an archipelago called Vestmannaeyjar. We’ve visited these spits before, also known as the Westman Islands. This series of islands is home to the puffling patrols! But, unlike the nice grouping of islands that compose the greater part of Vestmannaeyjar, Þrídrangar is off in its own corner of the roiling sea.

The remoteness of Þrídrangaviti leads many to call it the most isolated lighthouse in the world.

The construction of Thridrangaviti Lighthouse is an incredible tale.

Built between 1938 and 1939, the engineers did not have the luxury of helicopters to reach the stacks. Instead, they took boats to the crags and had to climb Stóridrangur, which juts upward 120 feet above the churning ocean. Overseeing the process was Árni Þórarinsson, who conscripted mountaineers to be his engineers. He later recounted:

“The first thing we had to do was create a road up to the cliff. We got together experienced mountaineers, all from the Westman Islands. Then we brought drills, hammers, chains and clamps to secure the chains. Once they got near the top there was no way to get any grip on the rock so one of them got down on his knees, the second stood on his back, and then the third climbed on top of the other two and was able to reach the nib of the cliff above. I cannot even tell you how I was feeling whilst witnessing this incredibly dangerous procedure.”

The usage of “road” here is amusing. Rock climbers could not scale the final portion of Stóridrangur with gear, so they formed a human chain! They spent the next month camped in tents on top of the rock, sculpting the building by hand, as supplies came up the newly formed chain “road.” I find it difficult to imagine this scene, so I dug for any imagery of the initial construction phase, but the internet yielded nothing. The humans who achieved this feat were certainly salty dogs worthy of praise.

Three years later, they somehow managed to install electricity onto the compound. In 1942, in the midst of World War II, the lighthouse was officially commissioned and began beaming warning signals into the abyss of the Atlantic Ocean. In the 1950s, life got a bit easier at Þrídrangaviti, as a helipad went into the rock face. This airborne transportation remains the mode du jour.

Yes, unlike many of the craziest lighthouses on the planet, Thridrangaviti still operates!

A 13-foot red lantern perches atop a 13-by-13 whitewashed hut. Since the light sits about 112 feet above the water, it can be seen over nine nautical miles away (10.4 statute miles). Every 30 seconds, a long white flash precedes a white burst, keeping any wayward boats from the treacherous Icelandic rocks.

Unfortunately, tourist visits to this incredible location are currently not available. Fortunately, video footage of the lighthouse atop the stacks floats around the net. The Icelandic band KALEO filmed a live performance of their track “Break My Baby” on the helipad. If North Atlantic rock music isn’t your thing, you can watch a group of people fly in to maintain the structures of Þrídrangar.

How long would you last at the world’s most isolated lighthouse? Perhaps with a few puffin pals to keep one company, the stunning views might be worth a bit of sequestration.

Further Reading and Exploration

Incredible location for a lighthouse perched on a rock in Iceland’s wild surf – Iceland Monitor

Thridrangar Lighthouse Travel Guide – Guide to Iceland

Þrídrangaviti Lighthouse – Atlas Obscura

Þrídrangaviti Lighthouse – The Wanderers