Pico de Orizaba – Mexico’s High Point

Mexico does not often garner the reputation of a nation with a lot of mountainous splendor. The sandy biomes – deserts and beaches – yes. Soaring peaks – not so much.

As we learned when Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston visited the Sierra Madre, however, perhaps that non-mountainous stature is unwarranted. The Sierra Madre should be the Sierras Madre, as not just one range bears the name but three! The guts of Mexico – slice off the Yucatan Peninsula – are outlined by the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Sierra Madre Oriental, and the Sierra Madre del Sur. In the center of this triangle is the Mexican Plateau, itself averaging nearly 6,000 feet above sea level. Mexico City chuckles at Denver’s Mile-High moniker, hosting international association football matches and the Olympics at 7,350 feet above the oceans.

With all this height, it should come as no surprise that the ceiling of Mexico is quite tall.

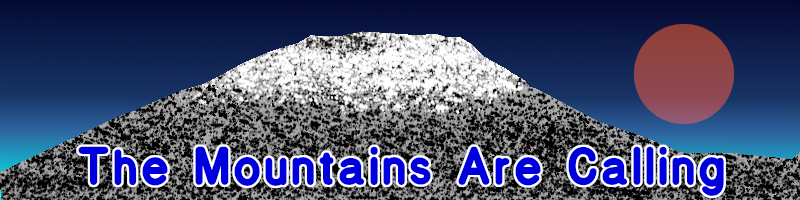

Rising 18,491 feet (5,636 meters) above sea level, the High Point of the country is Pico de Orizaba. Feast your eyes on this stratovolcano:

This crag goes by several names. Pico de Orizaba is the Spanish nomenclature. The city of Orizaba sits in the valley below, so humans went with the creative “Peak of Orizaba” to denote the acme of Mexico. Some of the indigenous names are a bit more flowery. The Náhuatl word is Citlaltépetl, which means “Star Mountain.” One idea for this designation comes from its snow-covered peak, which might seem to be an internal lodestar to the region. Interestingly, the Náhuatl people who live near Orizaba do not use Citlaltépetl; instead, they utilize Istaktepetl, which translates to “White Mountain.” Tlaxcaltecs have a third sobriquet: Poyauhtecatl. Leaning again on the star-like imagery, this word means “the one that colors or illuminates.”

The stats on Pico de Orizaba place it in some interesting spots on mountain lists. Its 18,491 feet are good for third place in North America, behind Denali in the United States and Canada’s Mount Logan. With all the massive peaks in these nations, an interesting quirk of geography arranges the top three spots to a mountain in each country. Mt. St. Elias – the second-highest point in Canada – lies just 26 miles from its parent and, still, Citlaltépetl manages to nestle between the elevations of the two. Further, Pico de Orizaba is the second most prominent volcano on the planet, after only Kilimanjaro. the High Point of Africa. Prominence is one of the major measurements of vertical rise in relation to a mountain’s surroundings. Draw a circle around a mountain such that no higher point rests within the circle, measure the rise from the edge of the circle to the peak, and you nab prominence. Pico de Orizaba’s prominence is an impressive 16,148 feet. In terms of topographical isolation – the distance one must travel to reach a higher peak – Poyauhtecatl comes in at 16th worldwide. One must go to Colombia to find a higher mountain.

These attributes indicate that the peak rises sharply above the surrounding terrain. No wonder it became Star Mountain.

The mount is a dormant volcano, which last erupted in 1846. Dormancy does not equate to extinction, so geologists believe Pico de Orizaba will erupt again at some point. Before the 19th century, the 1500s and 1600s witnessed a relatively active period, as the volcano spewed at least six times. Historically, this mountain has spurted at level 5 on the volcanic explosivity index, the grade of the Mt. St. Helens eruption. So, though it is relatively quiet at the moment, things can always get dicey for the region.

The volcano’s caldera sports elliptical diameters of 1,500 feet and 1,350 feet. The crater dips nearly a thousand feet inside the body. Many climbers note it seems to be bottomless!

Snow constantly covers this hole, an attribute that belies Mexico’s warmth and the mountain’s latitude, which is 300 miles south of the Tropic of Cancer. Pico de Orizaba even touts glaciers! Just one of three spots in Mexico with rivers of ice, the High Point is home to nine, including the largest in the country.

The combination of location and elevation creates a wide range of microclimates. At the base, a tropical climate dominates. As height increases, one can traipse through subtropical conditions, steppes, highlands, and even alpine tundra. This mixture of geography and altitude creates a rather stable, almost seasonless, environment. Blizzards can occur on the upper reaches nearly any time of year.

No recorded climbs of the mountain transpired before 1848, just two years after its last eruption. The first summit success came from two Americans, F. Maynard and William F. Raynolds. The latter would later lend his name to an expedition to map the area from the Dakotas to Yellowstone.

Today, the High Point draws thousands of climbers. Pico de Orizaba enjoys a reputation of relatively moderate for a mountain that features glaciers and high elevation. In 1936, nearly 50,000 acres surrounding the mountain became Pico de Orizaba National Park, which should protect the crag for generations of mountaineers.

Should one brave the slopes of Star Mountain, the intrepid climber would stand atop one of the Volcanic Seven Summits, the highest volcanos of each continent.

The apex of Mexico would also provide one’s eyes with a healthy dose of mountainous ineffability, perhaps no surprise from “the one that illuminates.”

Further Reading and Exploration

Pico de Orizaba, Mexico – Peakbagger

Pico de Orizaba – Summit Post

Volcano Pico de Orizaba – Encyclopedia Britannica

Pico de Orizaba – Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program

Orizaba – Stephen Brown/Sombrilla Magazine/University of Texas at San Antonio

Glaciers of Mexico – U.S. Geological Survey