Kilimanjaro

“No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.”

–Ernest Hemingway, The Snows of Kilimanjaro

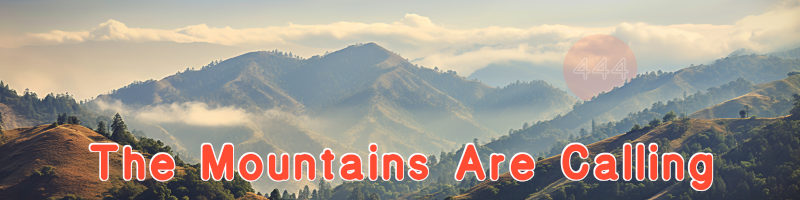

Rising 19,341 feet (5,895 meters) above sea level, Kilimanjaro not only rules over the continent but is also the tallest free-standing mountain in the world. This designation means Kilimanjaro is not part of a mountain range. Instead, the mountain achieved its loftiness because it’s a stratovolcano.

Kilimanjaro is so immense that three distinct volcanic cones compose its massive bulk: Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. The oldest acme of the volcano is Shira, which began erupting 2.5 million years ago. Kibo and Mawenzi started activity about a million years ago. Mawenzi and Shira are now extinct. Kibo, however, maintains activity, though scientists list its status as dormant. It has not gushed lava in approximately 150,000 to 200,000 years.

The highest part of the mountain rests on Kibo. The top spot on the crater rim is known as Uhuru Peak, which means “Freedom Peak” in Kiswahili. Kilimanjaro’s statistics garner a slew of superlatives. Being the highest mountain in Africa makes it one of the Seven Summits, but it’s also the highest volcano in the Eastern Hemisphere and the fourth most topographically prominent mountain on the planet (the height of a mountain’s summit relative to the lowest contour line encircling it but containing no higher summit within it). Kili rises 16,100 feet above the plateau surrounding the mountain, making it one of the tallest mountains in the world.

Because the crag rises so steeply above the surrounding plains, Kilimanjaro stretches upward through a number of distinct biomes. Savannas and brushlands yield to montane forest, which melds into a rainforest, which becomes heath, which blends into moorland, which becomes an alpine desert, before finally ending in an arctic climate. Those who wish to summit Kilimanjaro will trek through each!

Any attempt to reach the apex of Kilimanjaro by Indigenous humans during antiquity is lost to the ether. In 1889, the first Europeans – German geologist Hans Meyer and Austrian mountaineer Ludwig Purtscheller – ascended Kibo, after numerous failed attempts throughout the 1860s, 70s, and 80s.

Interestingly, Meyer and Purtscheller failed to reach the top of Mawenzi, which is a much more technical endeavor. Not until 1912 did two German climbers achieve the peak.

Today, seven routes lead to the top of Africa. Most people take about a week to make the sojourn. Though the trails do not require technical mountaineering expertise, the high altitude demands acclimatization.

In addition to inferior equipment and a lack of previous information, climbers before the 20th century faced a far more daunting climb than someone today: Kilimanjaro’s famous “snows.”

In 1936, Ernest Hemingway penned a short story, called The Snows of Kilimanjaro. The white cap of the great mountain is comprised of more than snow, however. Ice fields and glaciers covered the entirety of Kibo in the 1880s.

Unfortunately, between 1912 and 2011, 85% of the ice on Kilimanjaro melted and sublimated. Scientists believe most of the fields will disappear by 2040. By 2060, it’s highly unlikely that any ice will remain on the mountain.

The etymology of Kilimanjaro is unclear. European explorers believed the name to be the Kiswahili toponym. Early travelers noted that the name might equate to kilima + njaro, which could translate to the “mountain of greatness.” Others indicated potential meanings of “mountain of caravans” and “the white mountain.” All these origins contain no written support, as a few problems with all the possibilities exist. Njaro actually means “shining” in Kiswahili. Further, kilima means “hill,” the diminutive of milma. Even if these were the native terms for the mountain, they were likely garbled by Europeans at some point. No matter how the nomenclature arose, the name stuck.

Kilimanjaro is widely considered the easiest of the Seven Summits, which makes it a great “starter mountain” for someone who aspires to climb them all. Looking at this majestic volcano and thinking of it as a “starter mountain” puts the awesome scale of our planet in perspective. Only 61% of the hardy souls who begin the climb successfully summit. Three-quarters of trekkers experience acute mountain sickness due to the high altitude. The overall mortality rate hovers around 13.6 per 100,000 climbers.

Those who do manage to stand on the ceiling of Africa undoubtedly experience something profound. Hemingway’s story is framed with the metaphor of a leopard’s corpse being found on the summit. Why would a leopard go to the top of an extreme mountain? To Hemmingway, the leopard sought immortality, which it achieved by dying at such a high altitude that its body would not decompose. Is immortality, in some form, the reason we climb mountains? Certainly, in the neverending maze of our memories, summits – physical or those we construct for ourselves – seem to live forever. The summits we do not make, as in Hemmingway’s story, demand just as much memory space.

Someday soon, the snow-capped sentinel of the story will itself be a memory. Photos and tales will be the only way to know Kilimanjaro once contained multitudes of snow. In the geological scheme of eons, these ices are the definition of temporary, but they have easily attained immortality in the period of humanity.

Further Reading and Exploration

Kilimanjaro National Park – The Roof of Africa

Kilimanjaro National Park – National Parks

CLIMBING KILIMANJARO

The Zones of Kilimanjaro – NASA Earth Observatory

The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway